|

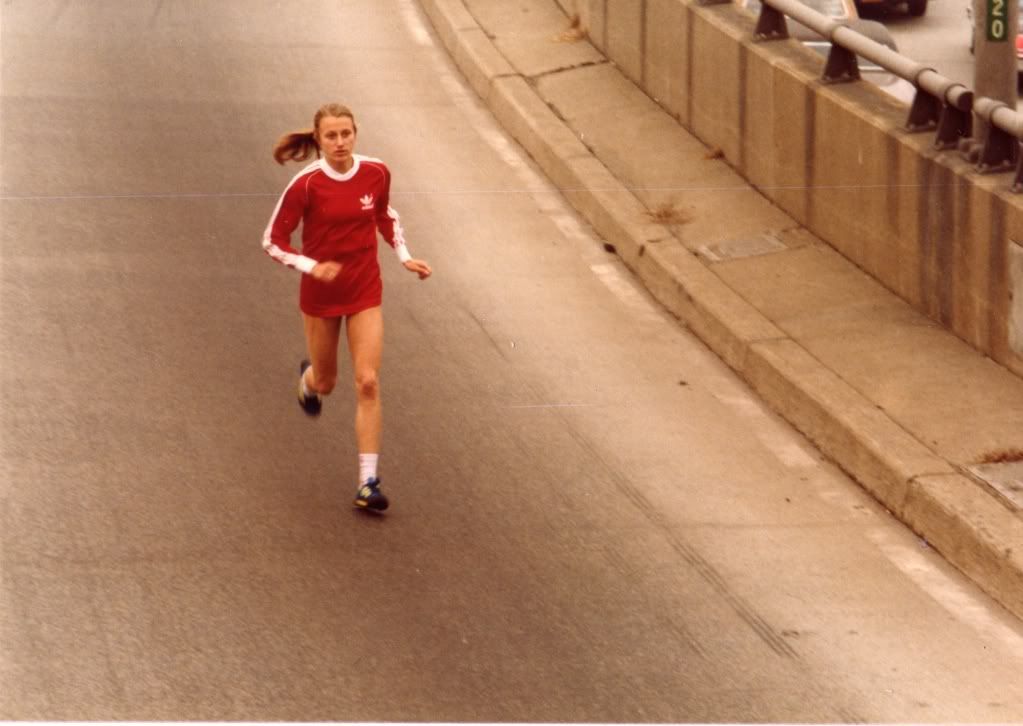

| Henry Rono set world records in 4 different events in 81 days, back in 1978 Photo: George Herringshaw http://contrameta.com/henry-rono-el-dios-de-los-estadios-gano-la-carrera-al-alcoholismo/ |

Henry was born in Kaptaragon, at the Nandi district the 12th February 1952. As he was 7, his father died in an accident, while driving a tractor. Then he moved with her grandmother and had to tend cattle so he joined a classroom later than usual and could not graduate from high school until he was 22. The sports he practised at the time where soccer and volleyball. Yet one day in 1971 he heard Kipchoge Keino was coming to run to a nearby place. Despite he was living just three miles away, Rono had never seen the renowned star and thus went to the meeting. After the magnificent impression he received from watching the Olympic champion, Henry Rono decided to become a world class athlete like him. The Kaptaragon youngster started training on his own without any coach, building up his running endurance patiently. (1) His steady progression came to the attention of the national team officials. He was selected to compete at the steeplechase in Montreal

That year he was conceded a scholarship in the United States and in the fall took a flight to study Industrial Psychology at Washington State University 90 miles a week, with brisk roadwork in the early mornings and intervals on selected afternoons. The athlete used to listen to his own body, deciding when the right moment to push was and which days it was better to go slower, in a typical Kenyan way, heir of Velzian and Lydiard. The ephemeral Kimobwa set a new 10.000 world record in 1977, which Rono would improve the following year. The latter would collect six NCAA titles, including three in Cross country, two at the 3000m steeplechase and another one at the 2 miles indoors. His performance at the steeplechase in 1978 is still a championship record.

1978, his sophomore year, was the stellar one of Henry Rono. During the spring, in a span of 81 days, he would successfully culminate his ferocious assault to four world records at the 5000m in Berkeley, California (13:08.4), 3000m steeplechase in Seattle (8:05.4), 10.000m in Vienna (27:22.4) and 3000m flat in Oslo (7:32.1); an unprecedented feat in track and field and never surpassed afterwards. Besides, all of them were accomplished without pacemakers and without any challenging rival. Rono would bite several seconds to the previous best in every race, up to eight at the 10.000m. In spite the huge progression in distance events in the last two decades, thanks to the likes of Haile Gebrselassie, Paul Tergat, Daniel Komen and Kenenisa Bekele, Rono’s marks still look more than respectable today. Especially, the 8:05.4 at the steeplechase stood for 11 years and is still beyond the capabilities of all but a couple of chosen ones. In 1978 Henry Rono won no less than 31 consecutive races outdoor, and his streak was only put an end in the last stages of a very long campaign in September, by future Olympic champions Bronislaw Malinowski and Steve Ovett. (2) That year the Kenyan athlete also shone at the Commonwealth Games, winning gold medals at the 3000m steeplechase and 5000m, and at the All-Africa Games, where he grabbed two more titles, again at the steeplechase and at the 10.000m.

Not quite at the same marvellous form, Rono still kept a good level during the four next seasons, achieving a last world record in 1981, improving his 5000m timing further to 13:06.20. The Nandi runner talked about his confidence in dipping under 8 minutes at the steeplechase, under 13 at the 5000m and under 27 at the 10.000m. (3) He was the first athlete in setting such ambitious targets. For sure he was gifted enough for this and more. It is worthy to consider, even in his magical season he states he was just 85% fit, and always had to dedicate plenty of time to his academic duties. Therefore he still had a lot of room to improve. However reality was much harsher: he was denied again his participation at the Olympic Games, because of a new boycott, and soon came his tragic fall.  |

| Henry Rono in 1978, his groundbreaking year Photo: George Herringshaw http://www.sporting-heroes.net |

Henry Rono felt as “a fish out of the water” and also as “a fish swimming among the sharks”. (5) In 1981 he wanted just concentrate in getting his degree but people around was pressuring him to make him race in as many places as possible. It was about the time another athlete, with great personality, Edwin Moses, would deceive all expectations not competing in one year, to fully focus in his studies in Physics, then would found Utopia Track Club with just two members: he and his friend and then roommate Henry Rono. (6) Unfortunately, the Kenyan was not as wise to deal with that interested world of corrupted coaches and unscrupulous agents and promoters. He felt they never thought of him as a person, about what he really wanted. Instead, he was treated just like a moneymaking-machine. (3) He took personal all those things and was affected in a way he lost altogether his balance, embracing a bottle as a solution. Famously, Rono had been drinking all the previous night, before achieving his last world record in 1981. So immense was his talent. In the following years the Kenyan champion would often appear in a pitiful condition at the meetings or would not appear at all. Among pizzas, quiches, beer and whisky, with his weight almost doubled up and a deteriorated wealth, soon it was impossible to keep competing.

Despite his six figure contract with Nike, all the money was quickly gone, siphoned by Athletics Kenya, European agents, meeting directors and by his own addiction and failed investment in real-estate. Thereafter, the living ghost of the old champion went from friends’ houses to rehabilitation clinics in different towns all across the country, when he was not arrested for driving drunk. Eventually he would temporarily join a homeless shelter at Washington D.C. and Salt Lake City Beaverton , Oregon Portland

Nonetheless, Henry Rono never quit in a race and in the turn of the century his struggles had brought him to a newly recovered life, no more a victim of the alcohol. He has started running again, losing many of his 220 pounds . Now in his fifties, Rono is competing in races in the Masters category, hoping to improve the mile best and set his sixth world record, a very long way from the fifth one. Besides he was admitted as a coach, and also as a special education teacher in an Alburquerque high school. Guiding athletes, the Kenyan is highly appreciated by his trainees: “He seems to understand the little things the body goes through, what the body needs. I think that must come from the fact he was not in shape all the time during his career. Being in shape or out of shape, he had to figure a way to get back.” On the other hand, Rono is also admired as a person: “He is really selfless. He gives us a lot of personal attention and he is very optimistic, the most optimistic person I have been around.” (5) Recently, Rono had accepted a job to train in Yemen

|

| Henry Rono, joining forces with the new generation of track and field Photo: Henry Rono https://plus.google.com/106120406482777402239/posts |

"I learned my mind was too small and weak. I was not able to handle or channel the energy in the proper place. I learned how you abuse yourself when you are successful. You think you can handle all that happens because you are a champion and champions handle things. I used to win races when I was drinking. Who is (to tell) me I am an alcoholic? ... My first profession is sports. My second is teaching. My ability, my talent of running is something I want to maximize while I am still at the age I can. I want to use it the right way this time around. Before, I do not think I used it properly because my life was mixed up, with my lifestyle in college, with alcohol, with struggling in the American culture. I understand it all better now." (9)

(1) http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1093730/1/index.htm

(2) http://www.team-rono.com/london-times-april-2007.php

(3) http://www.trackandfieldnews.com/archive/Interviews/henry_rono.pdf

(4) http://www.team-rono.com/rono-latimes-march-2007.php

(5) http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20070330/news_lz1s30back.html

(6) http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1122366/6/index.htm

(7) http://www.team-rono.com/life-that-ran-away.php

(8) http://www.team-rono.com/henry-rono-past.php

(9) http://www.team-rono.com/champion-survivor.php

(2) http://www.team-rono.com/london-times-april-2007.php

(3) http://www.trackandfieldnews.com/archive/Interviews/henry_rono.pdf

(4) http://www.team-rono.com/rono-latimes-march-2007.php

(5) http://www.signonsandiego.com/uniontrib/20070330/news_lz1s30back.html

(6) http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/vault/article/magazine/MAG1122366/6/index.htm

(7) http://www.team-rono.com/life-that-ran-away.php

(8) http://www.team-rono.com/henry-rono-past.php

(9) http://www.team-rono.com/champion-survivor.php